A Different Kind of GUI

“In the beginning was the command line.”

But then the command line became graphics and dwelt among us. From its earliest days, Apple privileged the lay user over the technical one, regarding the need to understand technical details as friction. With the Lisa and the Macintosh, Apple picked up where Xerox Palo Alto Research Center left off. The guiding principles of intuitiveness and discoverability led Apple to replace the command line interface (CLI) with the graphical user interface (GUI), featuring windows, menus, icons, and a pointing device (WIMP).

For these historical reasons, the GUI has always been pointer-driven, at least with respect to computer operating systems. Apple has only recently begun the transition to something new: iOS’s direct manipulation interface; still a GUI, but no longer driven by the same windows or menus or a pointing device. With this transition, Apple achieved its oldest dream more successfully than anyone anticipated. And it now seems to be pulling the rest of its product line into that dream. To use Steve Jobs’ terminology, they’re slowly transitioning out of the “truck” business.

The Mouse

It’s enlightening to consider what made the mouse such an indispensable companion to the GUI for so long.

- It’s intuitive. It’s easy to grasp the basic concept that the cursor is an extension of the hand, that its motion corresponds to the motion of the mouse.

- All interactions are built on a minimal set of axiomatic actions: move, hover, click, release, and drag.

- It provides highly precise and unrestricted motion of the cursor, as opposed to a joystick, which limits the cursor’s direction and velocity.

With careful application of the WIMP metaphor, these features made every aspect of a GUI accessible to the user. But this was only the minimal set afforded by the technology that was available at the time. With touch screen technology and the direct manipulation paradigm, Apple has not just removed an entire layer of abstraction, but also reduced that minimal set of actions even further to a more intuitive level: tap, swipe, and pinch. The resulting interface is qualitatively more intuitive and trivially easy for new users.[^1]

But restricting the minimal set of actions that far has implications that I think Apple is only starting to realize. With such a limited interaction bandwidth, for example, any given complex action has to take a correspondingly large number of sequential inputs. Apple’s way of mitigating this effect in iOS appears to be gestures, some of which, like five-finger pinch, are frankly ridiculous. Traditional desktop GUIs mitigate this by overloading the basic controls with incrementally added extra functionality that breaks metaphor: double-click, right-click, the scroll wheel, any number of additional mouse buttons. These are all extremely useful additions (because they increase the interaction bandwidth), but this phenomenon is actually part of what makes modern desktop GUIs inaccessible to novices and is why I imagine Apple has traditionally been so resistant to these kinds of innovations. But I think the underlying problem isn’t simply the tendency for cruft to accumulate, but the severely limiting nature of the metaphor to begin with. iOS, just a few years old, already contains more undiscoverable, out-of-metaphor inputs (gestures) than discoverable strictly in-metaphor ones.

But even aside from the unintuitiveness, there are a lot of reasons not to like the mouse:

- The arbitrary motion of a mouse cursor makes the effort analog, as opposed to the digital motion of keying. Commands, even repetitive ones, can’t be relegated to muscle memory the way command line commands or keyboard navigation can.

- Because of this, mousing is a conscious process. Hitting precise targets takes a lot more cognitive effort and close attention than keying.

- Moving the mouse hand back and forth between mouse and keyboard is often an annoying cognitive task-switch and that breaks flow.

- The requirement of moving back and forth between mouse and keyboard creates friction for typing. And since typing is one of the main ways of producing content, this friction is a particular type that only applies to production and not to consumption.

- It’s slower, or feels slower. (According to Bruce Tognazzini, Apple R&D found that mousing is in fact faster than keyboarding. This strikes me as highly dubious today not only for all the reasons given above, but also because the article is from 1989 and the research is presumably from before that. I believe the research was also done on non-expert users.

- While the high degree of precision afforded by the mouse is a boon to applications that benefit from it, as the dominant mode of interaction, it forces that level of precision on every transaction. For every dialogue box with two simple choices, for example, the user still must traverse an arbitrary distance and hit a cursor target that is tiny relative to the rest of the screen, which is, for the transaction, completely unused. So to make an input that’s essentially a binary 0 or 1, the user in real terms has to make a huge, well-calibrated, cognitively expensive analog input that’s largely wasted.

With OS X 10.7 Lion, Apple presents a clear and well-documented iOSification of OS X.[^2] A prominent sign to me is the seeming move toward deprecating the mouse, replacing and adding functionality with touchpad gestures. I empathize with the desire to leave the mouse behind. But where some of the iOS gestures are quite silly, the decisions Apple has made about Lion’s touchpad gestures are strange in a different way. I’ve discussed before Apple’s attempt to render the direct manipulation interface of iOS on the fundamentally indirect interface of the desktop. But aside from that, these gestures are no more efficient or discoverable than keyboard shortcuts and they do make you move your hand off the keyboard. While they are arguably a bit more intuitive and reminiscent[^3] of a real touch-based direct manipulation input system, it’s at heart really just a case of trading one set of undiscoverable metaphors for another. At least with keyboard shortcuts, it’s possible to expose functionality because the keys have a conventional labeling system built in. Gestures do not. I don’t see any real way to reconcile the inherent and fundamental difference between the two paradigms (direct and indirect) with the ergonomic constraints of different types of computing. Maybe Apple’s solution will be to further marginalize the needs of the technical user and simply move to a touch-only interface, with touch-screen laptops as their physically largest products. It’ll be interesting to see.

Building Blocks

But if this does mark the beginning of the end of the pointing device-driven model for consumer computing, it seems like a good time to rethink the technical user’s computing experience, unburdened by the need to cater to the novice or non-technical user. While the CLI seems to be regaining prominence and popularity among some subset of users, I don’t think a return to the command line is practical. The GUI has introduced some concepts and workflows that are very powerful. As real computers with dedicated input devices become more and more relegated to technical users, maybe a more robust but less intuitive interface becomes more viable. In fact, maybe we can abandon ‘intuitiveness’ as the primary motivator or at least stop defining the word as minimal interaction bandwidth.

Some starting points:

-

A purposefully high-bandwidth interaction model, i.e. a large but consistent set of initial undiscoverable actions to learn, that, at best, isn’t meaningfully less ‘intuitive,’[^4] but instead simply has a learning curve with a different shape.[^5]

-

The mouse is too powerful to get rid of entirely. There are many applications for which it is an ideal or at least very appropriate input device, such as graphics rendering, photo manipulation, and first-person shooters. So, to minimize travel between mouse and keyboard, functions of the mouse and the mouse-hand side of the keyboard should overlap as much as possible. These probably include: motion and selection.

-

I’ll revisit 10/GUI again, for some of the fantastic insights therein:

- Single axis of windows (Con10uum).

- Different levels of interaction.

-

Direct manipulation interfaces suggest that cursors are unnecessary. In our thought experiment, they would probably exist only in certain applications, specifically mouse-based ones.

-

We can draw inspiration from keyboard-only UIs.

- Vim is a venerable text editor that I’ve recently converted to. Its interface is modal, and its main mode of operation is through a command-based console.

- Windows’ keyboard access of menus, with visual indicators.

Fresh Start

My initial idea doesn’t stray too far from traditional WIMP systems. We’ll retain the windows, icons, and menus, but relegate the pointing device to only when necessary or appropriate. Let’s start with windows:

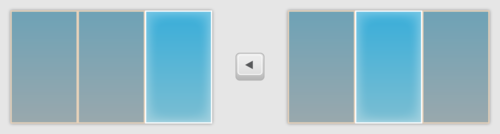

I’ll steal Con10uum’s single axis for windows with no allowance for vertical resizing, since I agree that the extra axis really only adds to the clutter and complexity.

Without a cursor, we navigate by using four directional keys on the keyboard, which I’ll just call [left], [right], [up], and [down], to select and highlight whole objects e.g. windows, more like navigating console game menus:

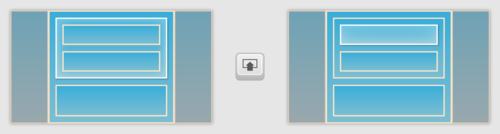

In this single axis system, z-order is really the same as horizontal order. So we’ll use z-order in a different way, by adding nested elements, and two more directional keys: [in] and [out].

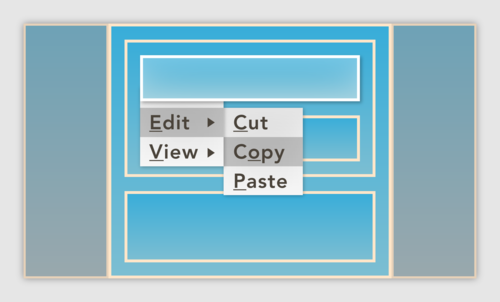

With any element selected in the UI, we can hit [menu] to invoke a consistent menu of possible actions to take on the element, with a corresponding key or sequence of keys for each action.

This makes possible command sequences that can become unconscious, relegated to muscle memory in the same way typing words can be. It makes movement sequences equally unconscious, as any Vim user will tell you. The benefits of making these into unconscious processes are many. Not only are they potentially faster and less interruptive to cognitive flow, but they can accumulate in a way that analog pointer-based UIs cannot. Once you learn the sequence for a particular menu command and use it enough to internalize it, you no longer have to think about it and can then spend that cognition on learning a new sequence. Learning to use the interface becomes an almost linguistic exercise. Pointer-based UIs can never reach this level because every action, every invocation of a menu or icon is a conscious act that demands much more attention.

Vim gives us other directions to explore with a primarily keyboard-driven interface. The basic principles of fewest number of key presses and proximity to the home row keys seem like good ones. Also, shortcuts to specific locations, e.g. the [os] key would take you directly to the operating system level and the [application] key to the application level. We can also take Vim’s concept of iteration, so [5], [left] would take you left five times. While Vim lives on the far end of a brutal learning curve, it’s a rich source of insight into how powerful a user interface can be when discoverability and intuitiveness are cast aside.

Starting with a high-bandwidth interaction model at the OS level has the added benefit of leaving fewer UI decisions to applications. A user can access more actions through a consistent menu/key sequence throughout the system, obviating the need to learn new keyboard shortcuts and interactions for each new application.

This is just a rough draft of an idea.

It’s an attempt to start thinking in ways unbound by the conventions we’ve been living with for decades. I imagine there are many different directions one can take, starting from the new assumptions we are allowed post-mouse.

The implications of a system like this are probably too big to patch onto the systems we have now. There would be a keyboard-driven interface analog to Fitts’s Law that would have implications for application design as well as operating system design. E.g. an application designer would always want to minimize the number of key presses it would take to move from any location to any other location, which would require a careful balance between breadth and depth of element distribution.

Anything in the near future will probably have to look a lot more like what we already have, and be filled with the compromises that we see in Lion and early demonstrations of Windows 8. But recent advancements provide us with a new context in which to fundamentally reconsider human computer interaction. There’s never been a time when it was more possible to try something truly new, or to more significantly change the landscape of future computing. My fear is that the trend toward simpler, more tightly controlled, narrower user experiences optimized for passive consumption will dominate. My hope is that we use the opportunity to create user experiences that encourage more active consumption, more substantial production, a generally richer, denser, deeper world.

Illustrations by Chris Klink.

Further Reading

- Christopher Mims. “Is the Desktop Having an Identity Crisis?”. MIT Technology Review. July 18, 2011.

- Wikipedia. “History of the GUI”.

- Jeremy Reimer. “A History of the GUI”.

- Brad A. Myers. “A Brief History of Human Computer Interaction Technology”. ACM interactions. Vol. 5, no. 2, March, 1998. pp. 44–54.

Notes

[^1]: Arthur C. Clark famously said: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” An abstract description of how this works is that a new technology is initially simple, then accumulates additional functionality. As its functionality grows, its operation becomes more complex. It then requires a more expert user to take advantage of the added functionality. But after a certain point, further advancements address this complexity of operation by internalizing it. This makes the technology simple to use for lay users, but in an opaque, ‘magical’ way.

[^2]: John Siracusa’s review of Lion is probably the best starting point, and this Mac Observer article discusses this as well.

[^3]: The mapping between iOS’s direct manipulation and Lion’s indirect manipulation via touchpad is weird. Nothing in iOS maps to moving the cursor around by dragging your finger across the touchpad. Scrolling with one finger in iOS, maps to dragging with two fingers in Lion. Touching in iOS maps to pressing down harder on the part of the touchpad that you’re already touching in Lion. And that’s not even getting into the crazy gestures. I think this actually produces a UI “uncanny valley” effect.

[^4]: If you think back to your first experience with a mouse, or watching someone’s first experience, you might agree that the mouse actually isn’t particularly intuitive so much as it is familiar.

[^5]: This observation is probably more broadly applicable. For example, languages with simpler grammars are probably easier to learn, but less powerful in terms of conveying a lot of subtle information in the shortest amount of time. I don’t have the knowledge or resources to explore this properly, though.